How the gospel of Barnabas survived

or: Verify your references

Op de webpagina barnabas.sabr.com (islamitische referentiepagina volgens de engelstalige wiki) staat een stuk met de titel: How the gospel of Barnabas survived. De info die hier wordt verstrekt is grotendeels naast de kwestie. Het lijkt wel alsof het hele wetenschappelijk onderzoek aan de opstellers van deze pagina is voorbijgegaan. Ik heb mij daarover eerst verbaasd, maar er blijkt een simpele verklaring voor te zijn. De moslimwereld lijdt nog steeds onder het feit dat de wetenschappelijke uitgave van L.& L. Ragg (1907) reeds in 1908 in het Arabisch is uitgegeven door Rashid Rida (vertaald door Khalil Sa’adeh)1. Op zich mooi, ware het niet dat deze editie een aantal wonderlijke toevoegingen / wijzigingen bevat. 1. De lange wetenschappelijke inleiding van Lonsdale Ragg is door Sa’adeh ingekort en bevat veel onjuistheden. 2. De uitgever, Rida, voegt er een eigen inleiding aan toe waarin hij stelt dat hiermee “het authentieke Evangelie” gevonden is.

Vanaf het allereerste begin is dit evangelie een argument in de ‘strijd’ met de christelijke apologeten.2 Daarna is – en dit tot de dag van vandaag – deze uitgave geregeld (clandestien) herdrukt. Hierdoor is er aan moslimzijde niet gesnoeid in de wildgroei aan legendes die er reeds bestonden rond Barnabas (het christendom is een fabricator legendarum als het om haar eigen geschiedenis/heiligen gaat) en die door Lonsdale Ragg in zijn inleiding juist aan een uitgebreid en kritisch onderzoek is onderworpen. Men heeft de claim ‘verum evangelium’ (afkomstig van de auteur van het Barnabas-evangelie) op gezag van Rashid Rida voor waar aangenomen (vaak nog met ‘klok-klepel’-effecten als de ene uitgever de andere afschrijft). Om daarin toch wat te saneren, druk ik hieronder de tekst van barnabas.sabr.com af met annotaties op grond van mijn eigen onderzoek naar en lezing van de tekst. Mijn annotaties in het rood. 3

- Vooraf: Het feit dat men in de tekst kerkvaders en anderen citeert, maar geen bronnen vermeldt, moet bij u – als kritische lezer – de nodige belletjes doen rinkelen (c.q. alarmbellen doen afgaan). Voor elke tekst die wetenschappelijk wil zijn geldt: vermeld de bronnen, die je citeert.

- Verder: Er is een pseudepigrafische Brief van Barnabas (2de eeuw). Dat betwist niemand. Maar die tekst heeft niets te maken met die Evangelie van Barnabas. Inhoudelijk staan ze zelfs tegenover elkaar (de brief is ‘gnostisch’ en spreekt negatief over de Torah/de Joodse wet, die in het Evangelie van Barnabas juist wordt verdedigd (besnijdenis en spijswetten!).

- De historische Barnabas was een Jood (uit de stam van Levi), afkomstig van Cyprus. Zijn echte naam schijnt Jozef geweest te zijn. Hij was een belangrijke figuur in de eerste christelijke gemeenschap, maar hoorde niet tot de inner circle van de 12 discipelen/apostelen. Hij is vooral bekend uit de bijbel als ontdekker en metgezel van Paulus, die hem in één van zijn brieven trouwens ook een ‘apostel’ noemt. Ze zijn samen op ‘missiereis’ geweest, o.a. naar Cyprus.

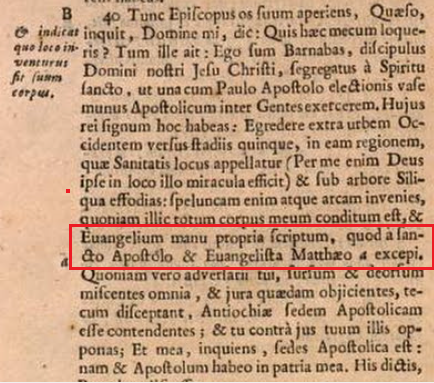

- De tekst hieronder citeert allerlei legendes rond Barnabas (allemaal laat 5de eeuw, begin 6de eeuw). Deze hebben hun oorsprong in de vondst van de beenderen van de ‘heilige Barnabas’, toevallig precies op het moment dat de bisschop van Cyprus zijn bisschopszetel wil vrijwaren tegen de claims van de bisschop van Antiochië en daarvoor een ‘apostolische’ legitimatie nodig heeft: Zijn kerk moet gesticht zijn door een apostel, en het graf van die apostel (of minstens een belangrijke reliek) moet zich op zijn grondgebied bevinden. Precies op dat moment vindt hij Barnabas, intact en wonderdoend aanwezig op zijn eiland. Het handgeschreven evangelie op z’n borst dient als identificatie-legitimatie van de beenderen. Overigens zijn alle legenden eensluidend op één punt: het betreft het Evangelie van Mattheüs.

How the gospel of Barnabas survived

The Gospel of Barnabas was accepted as a Canonical Gospel [not true] in the Churches of Alexandria till 325 C.E. Iranaeus (130-200) wrote in support of pure monotheism and opposed Paul for injecting into Christianity doctrines of the pagan Roman religion and Platonic philosophy [nonsense]. He had quoted extensively from the Gospel of Barnabas in support of his views [He did not. Where are the quotes? Give the references]. This shows that the Gospel of Barnabas was in circulation in the first and second centuries of Christianity. [If the suppositions are untrue, the conclusions are not valid.]

In 325 C.E., the Nicene Council was held [Correct], where it was ordered that all original Gospels in Hebrew script should be destroyed. [Not correct]. An Edict was issued that any one in possession of these Gospels will be put to death. [Not correct: Several Jewish customs were banned, but the bible and the canon were not an issue.]

In 383 C.E., the Pope secured a copy of the Gospel of Barnabas and kept it in his private library. [Nonsense, based on the 5th century legend: see below]

In the fourth year of Emperor Zeno (478 C.E.) [From this point forward the classic legend about Cyprus and the miraculous discovery of the bones of St. Barnabas by its bishop Anthemios is faithfully copied. This however is only a legend, invented/told with an ulterior motive: the ‘apostolic’ authentication of the independent Church of Cyprus, the remains of Barnabas were discovered and there was found on his breast a copy of the Gospel of Barnabas written by his own hand. (Acia Sanctorum Boland Junii Tom II, Pages 422 and 450. Antwerp 1698). [This is a reference to the extensive report of and commentary on this legend by the Antwerp Bollandists, i.c. Daniel Papebrochius, published as the Acta Sanctorum for the Month of June. The gospel mentioned in the legend is St. Matthew’s. See the image below. More about this legend in the footnote 4 The famous Vulgate Bible appears to be based on this Gospel. [Nonsense]

Pope Sixtus (1585-90) had a friend, Fra Marino [Unknown from any contemporary source. This section uncritically reproduces the pseudonymous preface to the Spanish translation/edition. It’s a literary device. As such it is as trustworthy as UMBERTO ECO’s introduction to ‘The Name of the Rose’… ]. He found the Gospel of Barnabas in the private library of the Pope. Fra Marino was interested because he had read the writings of Iranaeus where Barnabas had been profusely quoted.

The Italian manuscript passed through different hands till it reached “a person of great name and authority” in Amsterdam, “who during his life time was often heard to put a high value to this piece”. After his death it came in the possession of J. E. Cramer, a Councillor of the King of Prussia. In 1713 Cramer presented this manuscript to the famous connoisseur of books, Prince Eugene of Savoy. In 1738 along with the library of the Prince it found its way into Hofbibliothek in Vienna. There it now rests. [This section correctly describe the provenance of the Italian manuscript. It is based on the Introduction of L.L. Ragg (1907). The same goed for the next section]

Toland, in his “Miscellaneous Works” (published posthumously in 1747), in Vol. I, page 380, mentions that the Gospel of Barnabas was still extant. In Chapter XV he refers to the Glasian Decree of 496 C.E. where “Evangelium Barnabe” is included in the list of forbidden books. [Correct: Decretum Gelasianum. However, this does not imply existence, nor identity with the present text] Prior to that it had been forbidden by Pope Innocent in 465 C.E. and by the Decree of the Western Churches in 382 C.E. [Nonsense]. Barnabas is also mentioned in the Stichometry of Nicephorus Serial No. 3, Epistle of Barnabas . . . Lines 1, 300. [NB. This list only mentions the Epistle of Barnabas, not the gospel]. Then again in the list of Sixty Books

Serial No. 17. Travels and teaching of the Apostles.

Serial No. 18. Epistle of Barnabas.

Serial No. 24. Gospel According to Barnabas. [Correct. It is in the list. But again this does not imply existence, and even if it ever existed, this thus not imply identity with the present text.]

A Greek version of the Gospel of Barnabas is also found in a solitary fragment. The rest is burnt. [Not true, and if so: where is it? Provide the reference. Show it, and we will investigate it. There are two references to saying of Barnabas in texts from other Church-fathers, but around these quotes there is nothing mysterious]

The Latin [Error: must be Italian] text was translated into English by Mr. and Mrs. Ragg and was printed at the Clarendon Press in Oxford. It was published by the Oxford University Press in 1907. This English translation mysteriously disappeared from the market. [It did not. It was present in major University libraries, and was bought by interested scholars. It was never reprinted, because no demand from the market] Two copies of this translation are known to exist, one in the British Museum and the other in the Library of the Congress, Washington, DC. The first edition was from a micro-film copy of the book in the Library of the Congress, Washington, DC. [Nonsense]

This text is taken from the book published by The Quran Council of Pakistan, 11 A, 4th North Street, Defence Housing Society, Karachi-4, Pakistan. [Dear muslim friends: PLEASE. VERIFY YOUR REFERENCES BEFORE YOU PUBLISH]

- Rashīd Riḍā, ed., Injīl Barnāba, Cairo: Maṭbaʿat al-Manār, 1325/1907

- Luigi Cirillo and Michel Frémaux, Évangile de Barnabé, Fac-similé, introduction et notes, write on p v.: about Rashid Rida: “En le publiant, il le fit précéder d’une introduction qui le présentait comme l’évangile authentique.”. Zie ook h. 5 uit de monografie over Rashid Rida van Umar Ryad, Islamic Reformism and Christianity , dat gewijd is aan diens editie van het Barnabas-evangelie.

- Text downloaded from: http://barnabas.sabr.com/index.php/barnabas/503-how-the-gospel-of-barnabas-survived?hitcount=0

- In the legend, Barnabas appears in a dream to the Archbishop of Cyprus, Anthemios, indicating the place where his bones are buried. He receives precise directions and to authenticate the bones as relics of the Saint there will be a “handwritten copy of the Gospel of Matthew”. Suprised? You shouldn’t be: this is a quite common ‘authentication procedure’ for relics in those days. Of course the Bishop finds all things as prophecied, hurries to the Archbishop of Constantinople and the Emperor (Zeno). They are impressed and the Church of Cyprus is granted the ‘status’ of an independent (autocephaleous) Church. The patriarch of Constantinople demands the codex of St. Matthews Gospel. We are informed that it was written on paper made from the ’tree of life’. The broader context: The monophysite conflict in the Eastern Orthodox Church. This story also explains the relative independence and power (!) of the Cypriote Archbishop until today. The story is printed twice in the Acta Bollandista, both in Greek and in a Latin translation. I copied both on a separate page